Frequently Asked Questions

Questions which should probably be frequently asked by people who care about making sound decisions based on experimentation.

Table of contents

- What is Sample Ratio Mismatch?

- Why should we care about Sample Ratio Mismatch?

- How can we detect Sample Ratio Mismatch?

- What p-value threshold did the SRM Checker use?

- How common is Sample Ratio Mismatch?

- How can we fix Sample Ratio Mismatch?

- If an experiment has SRM, can we still analyse the results?

- Is the SRM Checker Chrome Extension still supported?

- How did the SRM Checker Chrome Extension used to work? (Now retired)

- Can we check for SRM if we don’t expect to split traffic equally?

- Can we check for SRM if we use bandits (or other kinds of Machine Learning)?

- Do we need to check for SRM if we use Bayesian statistics?

What is Sample Ratio Mismatch?

In A/B testing, a Sample Ratio Mismatch (SRM) is said to have occured when the observed proportion of the visitors sampled in a particular treatment group does not match the expected proportion of the visitors sampled; the two sample ratios (expected and observed) are mismatched.

For example, imagine we set up a test to split traffic equally between control (base) and treatment (a variation). Then further imagine that our analysis of the results of this experiment tells us that it has recieved 1.000 visitors. In this scenario, we would not be surprised to see approximately (since some slight deviation from a perfect split is to be expected) 500 of the visitors were assigned to control, and the remainder to treatment.

| Group | Expected | Observed |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 50% | 502 (50.2%) |

| Treatment | 50% | 498 (49.8%) |

We should, however, be surprised to see 600 of the 1.000 visitors assigned to control and only 400 to treatment. These allocation ratios, of 60% and 40% to control and treatment respectively, fall far outside of our expectations for an experiment which has been correctly configured to split traffic equally between control and treatment.

| Group | Expected | Observed |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 50% | 600 (60%) |

| Treatment | 50% | 400 (40%) |

This distribution of visitors is very unexpected. A sample ratio mismatch has occurred. It suggests that something has gone terribly wrong.

Why should we care about Sample Ratio Mismatch?

SRM tests can reveal serious data quality problems that change the outcomes of your experiments. Worse yet, most split testing platforms don’t alert users to SRM issues or suggest their experiments are broken.

Consider the results of an actual 50-50 split test:

| Group | Subjects | Conversions | % Conversion rate | % Lift |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 9463 | 235 | 2.48% | - |

| Treatment | 7681 | 193 | 2.51% | +1.18% |

Spot the difference in subjects? With an SRM p-value of 0.00000000000000022, this experiment clearly failed the test. And a post mortem revealed there were fewer IE & mobile users recorded in the treatment group. The cause?: The treatment took ~5 seconds longer to load and affected the tracking.

Imagine that ~2,000 subjects didn’t wait for the page to load. In that case, conversion rate could be impacted -18%.

| Group | Subjects | Conversions | % Conversion rate | % Lift |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 9463 | 235 | 2.48% | - |

| Treatment* | 9463 | 193 | 2.04% | -17.87% |

Without SRM tests, you could be missing some very big problems, like this and many more.

How can we detect Sample Ratio Mismatch?

To reliably and objectively detect Sample Ratio Mismatch, we need a statistical method to expres how “surprising” the observed split is, given the expected split. To do this, we can use a goodness of fit test to compute a p-value. When this value is very small, we reject the idea that the data are indeed a good fit, and conclude that a Sample Ratio Mismatch has occurred. (The approach used here is very similar to the standard hypothesis testing approach used to compare different variations in a standard A/B test.)

For example (using Python’s scipy.stats.chisquare), the first scenario describe earlier is indeed not surprising, as suggested by the computed p-value close to 1:

>>> from scipy import stats

>>> stats.chisquare([502,498],[500,500])[1]

0.8993431885613663

Conversely, the second scenario is very surprising. Here we get a p-value of approximately 0.00000000027.

>>> stats.chisquare([600,400],[500,500])[1]

2.5396285894708634e-10

What p-value threshold did the SRM Checker use?

The SRM Checker Chrome Extension used a threshold value of 0.01. If the computed p-value was lower than that, an SRM was flagged.

How common is Sample Ratio Mismatch?

Publically available information about the incidence of Sample Ratio Mismatch in experimentation platforms is limited. We are aware of only two companies which have publically released figures around this topic.

In “Automatic Detection and Diagnosis of Biased Online Experiments” (link), the authors briefly mention:

At LinkedIn, about 10% of our triggered experiments used to suffer from [sample ratio mismatch].”

In “Diagnosing Sample Ratio Mismatch in Online Controlled Experiments: A Taxonomy and Rules of Thumb for Practitioners” (link), the authors provide some more detail and insight:

During this study, and through quantitative analysis of experiments conducted within the last year we identified that approximately 6% of experiments at Microsoft exhibit an SRM. We illustrate this in Figure 2 where we show the variation of the SRM ratio among five products that run experiments at a large scale (ordered in descending order based on the number of experiments per product). Figure 2 reveals that this is an important problem to address as it happens frequently – for example, a product running ten thousand experiments in a year can expect to see at least one SRM per day.

Both LinkedIn and Microsoft have been actively addressing root causes of Sample Ratio Mismatch in their respective experimentation platforms for several years. These 6% and 10% figures should be considered in light of this fact.

It is obviously impossible to say what these numbers can tell us about the incidence of Sample Ratio Mismatch in general. However, it seems that SRM is quite prevalent, even in companies which are widely considered industry leaders in online experimentation.

How can we fix Sample Ratio Mismatch?

The answer to this question will depend on what is the root cause of the Sample Ratio Mismatch.

There are many potential root causes which may result in a Sample Ratio Mismatch. The KDD paper “Diagnosing Sample Ratio Mismatch in Online Controlled Experiments: A Taxonomy and Rules of Thumb for Practitioners” (link) describes a detailed taxonomy of known causes. The authors also briefly discuss ten rules of thumb for quickly diagnosing and categorization most of the causes in the taxonomy:

- Examine scorecards: If an SRM occurs in a subsample of users (e.g. in a triggered/filtered scorecard) and there is no SRM in the standard scorecard with all users in the experiment, it is likely that the trigger/filter condition is wrong in experiment analysis. Start by relaxing the filter to capture a wider audience and examine at what point the SRM problem occurs.

- Examine user Segments: If the SRM occurs in only one user segment, it is very likely that the cause of the SRM is localized to that segment. For instance, if the treatment is relying on some advanced browser capabilities like 256-bit encryption, the segment with older version of the browser might have an SRM.

- Examine time segments: If the evidence for SRM is strongest on day 1 of the experiment, and you do not observe the SRM after a longer time duration, the SRM is likely due to time related factors like caching during experiment execution, or delayed start of a variant in the experiment.

- Analyze performance metrics: If there is a large degradation in key performance metrics like time to load or crashes in the scorecard that has an SRM, then it is likely that the sign of this difference is real and is causing the SRM. For instance if the treatment increases page load time, then you may not get telemetry from some users who get the worst page load time, but you will still see regression when comparing treatment with control for those users for whom you do have telemetry.

- Analyze engagement metrics: If average engagement per user is higher in treatment compared to control, then it is likely that the root cause of the SRM is affecting less engaged users more, and vice-versa. For instance, in the case of Skype SRM example the root cause was due to a system bug impacting sessions with longer (more engaged) duration.

- Count frequency of SRMs: If many disparate experiments have an SRM, then it is likely that the root cause of the SRM is a systemic issue due to one or more factors from the taxonomy with a systematic widespread impact.

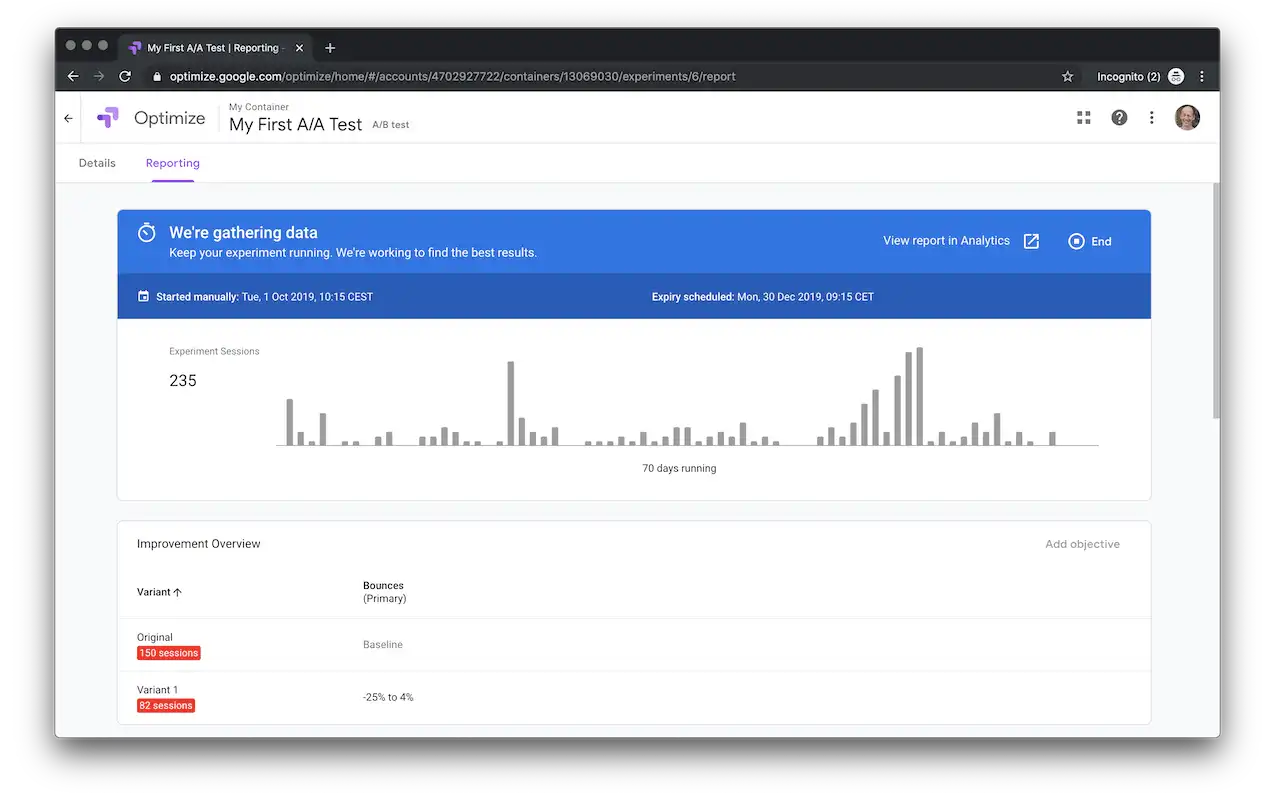

- Examine AA experiment: If an A/A experiment has an SRM then it is likely that one of the widespread factors is the root cause of the SRM, or the experiment is not actually an AA – for instance if you add extra telemetry in one of the variants then it is not an A/A as that variant might recover more users.

- Examine severity: If you observe a very large or very small sample ratio, then the root cause is likely to be affecting most users in the control or treatment, respectively. For example, if there are no users in one variation, then it is likely a telemetry issue where control variant or a trigger condition in control is not getting logged properly.

- Examine downstream: If your pipeline allows introspection of data at different collection and aggregation stages (e.g. in steps before the final scorecard), then comparing results at different stages may provide clues as to where the SRM originates.

- Examine across pipelines: If your experimentation system has two data pipelines, then compare the results of both pipelines. See “Democratizing online controlled experiments at Booking.com” (link) for more details. Also, examine debugging logs containing records that could not be merged in the pipelines. Differences in these point to log processing related SRMs.

Long story short: finding the root cause of a Sample Ratio Mismatch may require significant debugging and deep knowledge of which experiment platform abstraction is leaky.

If an experiment has SRM, can we still analyse the results?

Not without making additional assumptions and changing the way we calculate the results.

One idea is to apply the method described by Gerben and Green in their book Field Experiments as “extreme value bounds” (page 226). This approach relies on the idea that if we assume we know exactly how many samples are missing from our data, then we can calculate the “best case” and “worst case” scenarios that represent the most extreme results that are possible given the data we do have. These extreme values can then be said to bound the potential outcomes (hence the name “extreme value bounds”).

To calculate the extreme value bounds for a result, simply:

- Calculate how many samples we assume are missing. In a simple 50/50 split A/B test, the most likely estimate for this number is the difference in sample size between the variations. If A has 10.000 users and B has 9.000 users, then we are most likely missing 10.000-9.000=1.000 users.

- Assume the worst outcome for the missing samples. In the case of a conversion metric, we would assume none of the missing users converted. In our calculations of the treatment effect, we add the missing samples to our denominator, but the numerator stays the same. This is the lower extreme value bound. Following the example above, if previously B had 9.000 users and 900 conversions (so a 10% conversion rate), our lower bound would be the same 900 conversions over 9.000+1.000 users (a 9% conversion rate).

- Assume the best outcome for the missing samples. In the case of a conversion metric, we would assume all of the missing users converted. In our calculations of the treatment effect, we add the missing samples to our numerator as well as our denominator. This is the upper extreme value bound. Again following the example above, our upper bound would assume 900+1.000 conversions over 9.000+1.000 users (a 19% conversion rate).

Matt Gershoff suggested in a conversation in the Test & Learn Community that this method could be extended to calculate the confidence intervals for the upper and lower bound, not just the average treatment effect. This would make the bounds more conservative as they would include additional uncertainty around the effect.

Lukas Vermeer added that additionally one could overestimate the size of the missing sample (i.e. in the example above assume more than 1.000 users were missing) for an even more conservative estimate which also accounts for potential chance imbalance in assignment. It is not unlikely that in reality 10.300 users were assigned to B in the example above, and 1.300—rather than 1.000—went missing.

In practice—even without these more conservative extensions—these bounds are often so wide that they include the null and add little value. In some cases, the true treatment effect might be so large that the extreme value bounds do not include the null and can thus be used to inform a decision.

Is the SRM Checker Chrome Extension still supported?

No, the SRM Checker Chrome Extension has been retired and is no longer maintained.

How did the SRM Checker Chrome Extension used to work? (Now retired)

The extension previously ran in the background on supported experimentation platforms, extracting summary statistics and checking for Sample Ratio Mismatch. If an SRM was found, the page was modified in real time to alert the user.

Can we check for SRM if we don’t expect to split traffic equally?

Yes. The checker compares the expected split against the observed split. That split does not need to be equal.

For example, if a test was configured to split traffic 80/20, there would be no Sample Ratio Mismatch detected if a 80/20 split is indeed observed. Conversely, there would be a Sample Ratio Mismatch detected if the observed split was exactly 50/50, since this would be very unexpected given the 80/20 configuration.

Can we check for SRM if we use bandits (or other kinds of Machine Learning)?

In theory this is possible. In practice much more than just basic summary statistics alone are required to determine what split is to be expected when using adaptive sampling strategies, since this expectation will depend on the strategy as well as the observed data over time. For this practical reason, the SRM Checker Chrome Extension does not support these use cases (and likely never will).

Do we need to check for SRM if we use Bayesian statistics?

Yes. Most (if not all) of the causes of Sample Ratio Mismatch equally affect the validity of the results an experiment when using Bayesian approaches to analysing the experiment data. The SRM Checker Chrome Extension can therefore also be used to check for SRM on platforms which use Bayesian statistics.

Still have questions?